When THE THIEF had been in production for a few years Richard Williams hired Art Babbit and Ken Harris, two amazing animators from Disney and Warner Bros. to not only work on the film but to also instruct Williams and his animators on how to do it right.

Below is part one of a recorded interview between Ken Harris and Richard, circa 1975.

KEN: Ask the average guy to do an animation test, and he'll try to make a big production of it. He'll want to do a whole scene of a guy coming in and causing a fight, picking another guy up and throwing him out and all that sort of thing - instead of just doing a walk, or something simple. And then they get all lost in the timing and everything else. Then they get discouraged when you criticize them.

DICK: So they should just concentrate on walks?

KEN: Well, a walk is the first thing to do; I'll do other things too, but I wouldn't make a great production out of anything until you get pretty good at animating; Walks are about the toughest thing to do right. Don't try to do dancing and all this theatrical stuff until they get the basic thing down right; It's not easy; After you've flipped a fellow's drawings to see what's going on - then it's easy to tell him what to do; But it's pretty hard to come right out and say how to start animation. You've got to know what's in your mind; You've got to be an actor, really, because that's what you're doing - you're sort of acting with a pencil. You've got to learn to draw well enough to draw them - which is the hard part.

DICK: What if you already draw well?

KEN: There are a lot of terrific artists who'll never be animators, because they just don't know how to do it.

DICK: How do you learn to time the actions? If you're acting it out in your mind, how do you time it?

KEN: That takes experience. You just time it by timing it. You get to know how long it takes to do a thing the way you want to do it.

DICK: When you started, did you have stop-watches?

KEN: We had metronomes; You could set a metronome on 6's or 8’s or 10's if you wanted a walk or anything like that. We had Carl Stalling, the musician Disney first brought to Hollywood. Carl used to give us a lot of pointers on music timing. We would ask Carl about what music phrase or number of bars that he wanted to do a thing in. Also, the Director would time it out himself - the way he wanted to do it, and we would also confer with Carl in getting the music timing. Oh, learning timing comes so gradually; It's like Benny Washam's 12-frame yawn.

When you first start out animating something, it takes so long to make those drawings that you think, "Gee, whizz, this will take up a lot of screen time. It's taken me half a day to make 12 drawings, and that must make a long, slow yawn." Well, half a second for a yawn isn't very long, is it? It just takes experience in timing, and doing things, and tapping it out with a pencil - beating it out per foot, 'till you get to know.

DICK: You time things out way in advance, don't you? I notice that you put the numbers for your main drawings on the exposure sheet way in advance of where you are actually drawing.

KEN: Oh, yes. I time things out way ahead: I time things about 5 feet ahead sometimes. If I want a guy to do something, and I want him to land 'over there', 5 feet later, I'll number the drawings, and put the drawings down, and number the end one; Then I'll work up to it.

Say, it takes about 4 feet to do something; So I'd put drawing number 33 here; I need about 33 drawings in between there - on twos - that will make about 4 feet.

DICK: When you time ahead, I notice you even write down the exact numbers on the X-sheet - working in twos. You put the numbers down before you draw it?

KEN: If I figure it's going to be on twos all the way, I do. But if it's the kind of animation that needs some fast wallops or fast action in between there and here, well, you're going to have to use ones in there to do it. Normally, I work four drawings ahead - on normal animation; I make drawing number 1, and my next extreme will be number 5, then number 9. And maybe if it's faster, I'll put 5 closer to 1 and maybe I'd want the action to slow down, and I'd put 9 a long way from 5, and 13 a long way - then maybe 17 and 21 right close together as part of the speed.

That's for 'progressive' animation.

DICK: How do you learn to work that way? How do you learn to do just the extreme positions while working out what you want the in-betweener, or assistant to do?

KEN: Well, you know the timing. You know how long three in-betweens on twos is. If you make drawings 1 and 5, that's eight frames - so for animation, if you make a '1' here and '5' there, and you've got 3 here, that's going to be slow. And if this guy here comes forward really fast, I'd make 1 and 5 close together, and maybe 7 would be well over there, with maybe a 'long-headed' inbetween to zoom over here, and then he shouts or something there, and maybe I'll make that in five drawings. I figure, if he's talking, his head ought to go out, so I would draw that out there, then I might just draw the mouths in between, and nothing else - and let my assistant draw the in-betweens of the head going out. No use me wasting my time, you know.

If you had to do a lot of animation, and had to get out 35, 40, 50 feet a week - you could do it that way, with a good assistant.

Now, for instance, if you've got a 'progressive' scene where you want a guy coming in and maybe walking over and picking up something and carrying it over and putting it down and then coming back and getting…[missing]

I work about 4 drawings apart. 1 to 5 to 9 and so forth. Then, if the in-between (or breakdown drawing) looks too involved for the assistant to do, I will just make 3 or 7, and maybe make some ones some place.

But timing is just experience; That's the only way you can get it. You've got to get a feel for it - the way it ought to be. Like hand actions: Hold it out here for a certain length of time, bring it in, then it goes out, and then he brings it in again, or something; That's acting. You get that by studying guys like John Barrymore. In personality dialogue, that's very important.

DICK : So you get to know the length of time of a second. It’s completely set in your mind; You know exactly what you're going to do?

KEN: Yes, I know pretty much. And I know how many frames I need to accent something, and I know how many frames I need to slow out of it; A guy says something like, "Get going!", well, "get" would be this picture here, and here, and an in-between, and that's the accent, and when the head is up here you slow out of it. You don't just bang it back down again - you use maybe 6 to 8 drawings to get back to where you started it. But that's all timing that you've gotten by experience which you've had. You know how fast the film goes through. A stop-watch is good to time the length of scenes and such, but the stop-watch doesn't cut it down to a point where you can get a quick accent.

It’s like that guy where you made him shoot himself. You took some frames out of where his head went back when the bullet hits his head. You even could take all the frames out. If his head was here and he pulled the trigger, and his head went clear over to here without any in-between, it would work.

It works well the way it is - but if you want it to bang harder, and if it was a bigger bore gun, and you wanted a real blast you could just leave out the in-betweens.

Lots of times, we will take a little fish, or a humming bird going from one rose to another…this humming bird will flutter here and then, bang! - he's over there with maybe just one elongated blur on ones, and then a 'cushion'.

You can do almost anything by just starting something here and cushioning it way over here. You don't need any in-betweens.

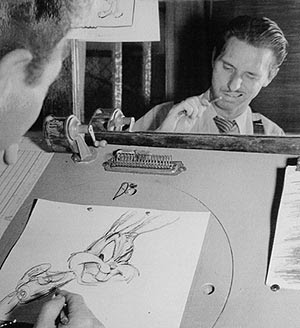

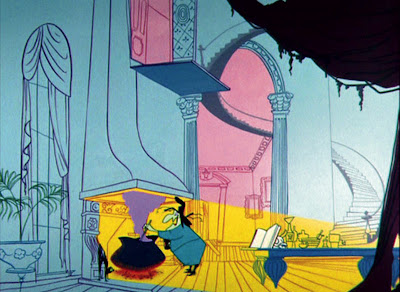

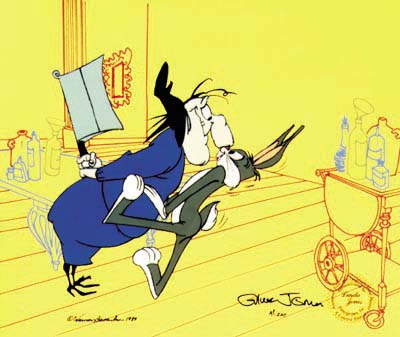

DICK: When I was 23 and I traced off your animation in 'Broomstick Bunny', I was surprised that where the witch went up in the air, you had her do an anticipation on the floor, for which you had 2 or 3 drawings, then POW! - you just cut to her way up in the air when she was laughing.

KEN: There's a lot of that in there.

DICK: You used 3 or 4 drawings of her getting ready to leave and then suddenly she was in the air, or just 'gone' entirely.

KEN: Yes, and instead of making a blur, or something we used to just leave hairpins where she was - and that gives you the effect of her leaving. We learned that from Disney, in a fish picture: He'd have these little fish swimming around and something would scare them, and they were gone - that's all - with just a few bubbles for the path they took.

But that just takes experience. A guy should gain that experience while he's an assistant, if he really bears down and watches animators.

COMING SOON: PART TWO OF THIS CONVERSATION

To learn more about Ken, visit this website, devoted entirely to him: Ken Harris, Master Animator.

- trevor.

No comments:

Post a Comment